Tuesday, 18 June 2024

TUZOIA OF THE BALANG FORMATION

This specimen was collected in October 2019. It is one of many new and exciting arthropods to come from the site. Balang has a low diversity of trilobites and many soft-bodied fossils similar in preservation to Canada's Burgess Shale.

Some of the most interesting finds include the first discovery of anomalocaridid appendages (Appendage-F-type) from China along with the early arthropod Leanchoiliids with his atypical frontal appendages (and questionable phylogenetic placement) and the soft-shelled trilobite-like arthropod, Naraoiidae.

Jianheaspis jiaobangensis, is a newly described trilobite also from the Lower Cambrian Balang Formation of Guizhou Province, China. While the site is not as well-studied as the Chengjiang and Kaili Lagerstätten, it looks very promising. The exceptionally well-preserved fauna includes algae, sponges, chancelloriids, cnidarians, worms, molluscs, brachiopods, trilobites and a few non-mineralized arthropods. It is an exciting time for Cambrian paleontology. The Balang provides an intriguing new window into our ancient seas and the profound diversification of life that flourished there.

Friday, 14 June 2024

TANGLEFOOT MOUNTAIN TRILOBITES

Brian Chatterton has been visiting the East Kootenay region for many years. In 1998, he and Rolf Ludvigsen published the pivotal work on the "calcified trilobites" we had begun hearing about in the late 1990s.

There were tales of blue trilobites in calcified layers guarded by a resident Grizzly. This was years before logging roads had reached this pocket of paleontological goodness and hiking in — bear or no bear — was a daunting task.

In his Cambridge University Press paper, Chatterton describes the well-preserved fauna of largely articulated trilobites from three new localities in the Bull River Valley.

All the trilobites from these localities are from the lower or middle part of the Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of the Elvinia Zone, lower Jiangshanian, in the McKay Group.

Access is via a bumpy ride on logging roads 20 km northeast of Fort Steele that includes fording a river (for those blessed with large tires and a high wheelbase) and culminating in a hot, dusty hike and death-defying 5-story traipse down a 35-degree slope to the localities.Two new species were proposed with types from these localities: Aciculolenus askewi and Cliffia nicoleae.

The trilobite (and agnostid) fauna from these localities includes at least 20 species that read like a who's who of East Kootenay palaeontology:

Aciculolenus askewi n. sp., Agnostotes orientalis (Kobayashi, 1935), Cernuolimbus ludvigseni Chatterton and Gibb, 2016, Cliffia nicoleae n. sp., Elvinia roemeri (Shumard, 1861), Grandagnostus? species 1 of Chatterton and Gibb, 2016, Eugonocare? phillipi Chatterton and Gibb, 2016, Eugonocare? sp. A, Housia vacuna (Walcott, 1912), Irvingella convexa (Kobayashi, 1935), Irvingella flohri Resser, 1942, Irvingella species B Chatterton and Gibb, 2016, Olenaspella chrisnewi Chatterton and Gibb, 2016, Proceratopyge canadensis (Chatterton and Ludvigsen, 1998), Proceratopyge rectispinata (Troedsson, 1937), Pseudagnostus cf. P. josepha (Hall, 1863), Pseudagnostus securiger (Lake, 1906), Pseudeugonocare bispinatum (Kobayashi, 1962), Pterocephalia sp., and Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Chatterton and Gibb, 2016.

It has been the collaborative efforts of Guy Santucci, Chris New, Chris Jenkins, Don Askew and Stacey Gibb that has helped open up the region — including finding and identifying many new species or firsts including Pseudagnostus securiger, a widespread early Jiangshanian species not been previously recorded from southeastern British Columbia.Other interesting invertebrate fossils from these localities include brachiopods, rare trace fossils, a complete silica sponge (Hyalospongea), and a dendroid graptolite.

The species we find here are more diverse than those from other localities of the same age in the region — and enjoy much better preservation.

The birth of new species into our scientific nomenclature takes time and the gathering of enough material to justify a new species name. Fortunately for Labiostria gibbae, specimens had been found of this rare species had been documented from the upper part of Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone — slightly younger in age.

Combined with an earlier discovery, they provided adequate type material to propose the new species — Labiostria gibbae — a species that honours Stacey Gibb and which will likely prove useful for biostratigraphy.

Reference: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-paleontology/article/abs/midfurongian-trilobites-and-agnostids-from-the-wujiajiania-lyndasmithae-subzone-of-the-elvinia-zone-mckay-group-southeastern-british-columbia-canada/E8DBC8BD635863E840715122C05BB14A#

Wednesday, 12 June 2024

PROBOSCIDEAN REMAINS AND THE MYTH OF ANTAEUS

|

| Tetralophodon |

Most of these large beasts had four tusks and likely a trunk similar to modern elephants. They were creatures of legend, inspiring myths and stories of fanciful creatures to the first humans to encounter them.

Beyond our Neanderthal friends, one such fellow was Quintus Sertorius, a Roman statesman come general, who grew up in Umbria. Born into a world at war just two years before the Romans sacked Corinth to bring Greece under Roman rule, Quintus lived much of his life as a military man far from his native Norcia. Around 81 BC, he travelled to Morocco, the land of opium, massive trilobites and the birthplace of Antaeus, the legendary North African ogre who was killed by the Greek hero Heracles.

The locals tell a tale that Quintus requested proof of Antaeus, hard evidence he could bring back to Rome to support their tales so they took him to a mound near Tingis, the ancient name for Tangier, Morocco. It was here they unearthed the bones of an extinct elephantoid, Tetralophodon.

Tetralophodon bones are large and skeletons singularly impressive. Impressive enough to be taken for something else entirely. By all accounts, these proboscidean remains were that of the mythical giant, Antaeus, son of the gods Poseidon and Gaea and were thus reported back to Rome as such. Antaeus went on to marry the goddess Tinge and it is from her, in part, that Tangier in northwestern Morocco gets its name. Together, Antaeus and Tinge had a son, Sophax. He is credited with having the North Africa city take her name. Rome was satisfied with the find. It would be hundreds of years later before the bones true ancestry was known and in that time, many more wonderful ancient proboscideans remains were unearthed..

Tuesday, 11 June 2024

CERATIOCARIS, YE KEN

Ceratiocaris is a genus of extinct paleozoic phyllocarid crustacean whose fossils are found in marine strata from the Upper Ordovician through to the Silurian.

They are typified by eight short thoracic segments, seven longer abdominal somites and an elongated pretelson somite. Their carapace is slightly oval shaped; they have many ridges parallel to the ventral margin and possess a horn at the anterior end.

This tidy specimen is from the Silurian mudstones that characterise the Kip Burn Formation with it's dark laminated silty bands. The lower part of the Kip Burn houses the highly fossiliferous ‘Ceratiocaris beds’, that yield the arthropods Ceratiocaris, Dictyocaris, Pterygotus, Slimonia and the fish Birkenia and Thelodus.

The upper part of the formation, the ‘Pterygotus beds’, contain abundant eurypterid fauna together with the brachiopods Lingula and Ceratiocaris. The faunas in the Kip Burn Formation reflect the start of the transition from marine to quasi- or non-marine conditions in the group.

Ceratiocaris are also well known from the Silurian Eramosa Formation of Ontario, Canada (which also has rather nice eurypterids). Photo credit / collection of: York Yuxi Wang and Tianyi Zhang

Joseph H. Collette; David M. Rudkin (2010). "Phyllocarid crustaceans from the Silurian Eramosa Lagerstätte (Ontario, Canada): taxonomy and functional morphology". Journal of Paleontology. 84 (1): 118–127. doi:10.1666/08-174.1.

M. Copeland; T. E. Bolton (1985). Fossils of Ontario part 3: the eurypterids and phyllocarids. Volume 48 of Life Sciences Miscellaneous Publications. Royal Ontario Museum. ISBN 0-88854-314-X.

Monday, 10 June 2024

FOSSIL BIRDS FROM VANCOUVER ISLAND'S SOUTHERN SHORES

|

| Stemec suntokum, Sooke Formation |

As well as amazing west coast scenery, the beach site outcrop has a lovely soft matrix with well-preserved fossil molluscs, often with the shell material preserved (Clark and Arnold, 1923).

By the Oligocene ocean temperatures had cooled to near modern levels and the taxa preserved here as fossils bear a strong resemblance to those found living beneath the Strait of Juan de Fuca today. Gastropods, bivalves, echinoids, coral, chitin and limpets are common-ish — and on rare occasions, fossil marine mammals, cetacean and bird bones are discovered.

Fossil Bird Bones

Back in 2013, Steve Suntok and his family found fossilized bones from a 25-million-year-old wing-propelled flightless diving bird while out strolling the shoreline near Sooke. Not knowing what they had found but recognizing it as significant, the bones were brought to the Royal British Columbia Museum to identify.

The bones found their way into the hands of Gary Kaiser. Kaiser worked as a biologist for Environment Canada and the Nature Conservatory of Canada. After retirement, he turned his eye from our extant avian friends to their fossil lineage. The thing about passion is it never retires. Gary is now a research associate with the Royal British Columbia Museum, published author and continues his research on birds and their paleontological past.

Kaiser identified the well-preserved coracoid bones as the first example from Canada of a Plotopteridae, an extinct family that lived in the North Pacific from the late Eocene to the early Miocene. In honour of the First Nations who have lived in the area since time immemorial and Steve Suntok who found the fossil, Kaiser named the new genus and species Stemec suntokum.

|

| Magellanic Penguin Chick, Spheniscus magellanicus |

Doubly lucky is that the find was of a coracoid, a bone from the shoulder that provides information on how this bird moved and dove through the water similar to a penguin. It's the wee bit that flexes as the bird moves his wing up and down.

Picture a penguin doing a little waddle and flapping their flipper-like wings getting ready to hop near and dive into the water. Now imagine them expertly porpoising — gracefully jumping out of the sea and zigzagging through the ocean to avoid predators. It is likely that the Sooke find did some if not all of these activities.

When preservation conditions are kind and we are lucky enough to find the forelimbs of our plotopterid friends, their bones tell us that these water birds used wing-propelled propulsion to move through the water similar to penguins (Hasegawa et al., 1979; Olson and Hasegawa, 1979, 1996; Olson, 1980; Kimura et al., 1998; Mayr, 2005; Sakurai et al., 2008; Dyke et al., 2011).

Kaiser published on the find, along with Junya Watanabe, and Marji Johns. Their work: "A new member of the family Plotopteridae (Aves) from the late Oligocene of British Columbia, Canada," can be found in the November 2015 edition of Palaeontologia Electronica. If you fancy a read, I've included the link below.

The paper shares insights into what we have learned from the coracoid bone from the holotype Stemec suntokum specimen. It has an unusually narrow, conical shaft, much more gracile than the broad, flattened coracoids of other avian groups. This observation has led some to question if it is, in fact, a proto-cormorant of some kind. We'll need to find more of their fossilized lineage to make any additional comparisons.

|

| Sooke, British Columbia and Juan de Fuca Strait |

While we'll never know for sure, the wee fellow from the Sooke Formation was likely about 50-65 cm long and weighed in around 1.72-2.2 kg — so roughly the length of a duck and weight of a small Magellanic Penguin, Spheniscus magellanicus, chick.

The first fossil described as a Plotopteridae was from a wee piece of the omal end of a coracoid from Oligocene outcrops of the Pyramid Hill Sand Member, Jewett Sand Formation of California (LACM 8927). Hildegarde Howard (1969) an American avian palaeontologist described it as Plotopterum joaquinensis. Hildegarde also did some fine work in the La Brea Tar Pits, particularly her work on the Rancho La Brea eagles.

In 1894, a portion of a pelagornithid tarsometatarsus, a lower leg bone from Cyphornis magnus (Cope, 1894) was found in Carmanah Group on southwestern Vancouver Island (Wetmore, 1928) and is now in the collections of the National Museum of Canada as P-189401/6323. This is the wee bone we find in the lower leg of birds and some dinosaurs. We also see this same bony feature in our Heterodontosauridae, a family of early and adorably tiny ornithischian dinosaurs — a lovely example of parallel evolution.

|

They are now in the collections of the Royal BC Museum as (RBCM.EH2013.033.0001.001 and RBCM.EH2013.035.0001.001). These bones do have the look of our extant cormorant friends but the specimens themselves were not very well-preserved so a positive ID is tricky.

The third (and clearly not last) bone, is a well-preserved coracoid bone now in the collection at the RBCM as (RBCM.EH2014.032.0001.001).

Along with these rare bird bones, the Paleogene sedimentary deposits of the Carmanah Group on southwestern Vancouver Island have a wonderful diversity of delicate fossil molluscs (Clark and Arnold, 1923). Walking along the beach, look for boulders with white shelly material in them. You'll want to collect from the large fossiliferous blocks and avoid the cliffs. The lines of fossils you see in those cliffs tell the story of deposition along a strandline. Collecting from them is both unsafe and poor form as it disturbs nearby neighbours and is discouraged.

|

| Sooke Formation Gastropods, Photo: John Fam |

The preservation here formed masses of shell coquinas that cemented together but are easily worked with a hammer and chisel. Remember your eye protection and I'd choose wellies or rubber boots over runners or hikers.

You may be especially lucky on your day out. Look for the larger fossil bones of marine mammals and whales that lived along the North American Pacific Coast in the Early Oligocene (Chattian).

Concretions and coquinas on the beach have yielded desmostylid, an extinct herbivorous marine mammal, Cornwallius sookensis (Cornwall, 1922) and 40 cm. skull of a cetacean Chonecetus sookensis (Russell, 1968), and a funnel whale, a primitive ancestor of our Baleen whales.

References:

Barnes, Lawrence & Goedert, James. (1996). Marine vertebrate palaeontology on the Olympic Peninsula. Washington Geology, 24(3):17-25.

Fancy a read? Here's the link to Gary Kaiser's paper: https://palaeo-electronica.org/content/2015/1359-plotopterid-in-canada. If you'd like to head to the beach site, head to: 48.4°N 123.9°W, paleo-coordinates 48.0°N 115.0°W.

Sunday, 9 June 2024

FOSSILS AND FINCHES OF MADAGASCAR

|

| Aioloceras besairiei (Collingnon, 1949) |

Madagascar has some of the most spectacular of all the fossil specimens I have ever seen. This beauty is no exception. The shell has a generally small umbilicus, arched to acute venter, and typically at some growth stage, falcoid ribs that spring in pairs from umbilical tubercles, usually disappearing on the outer whorls. I had originally had this specimen marked as a Cleoniceras besairiei, except Cleoniceras and Grycia are not present in Madagascar.

The beauty you see here measures in at a whopping 22 cm, so quite a handful. This specimen is from the youngest or uppermost subdivision of the Lower Cretaceous. I'd originally thought this locality was older, but dating reveals it to be from the Lower Albian, so approximately 113.0 ± 1.0 Ma to 100.5 ± 0.9 Ma.

Aioloceras are found in the Cretaceous of Madagascar at geo coordinates 16.5° S, 45.9° E: paleo-coordinates 40.5° S, 29.3° E.; and in four localities in South Africa: at locality 36, near the Mzinene River at 28.0° S, 32.3° E: paleo-coordinates 48.6° S, 7.6° E.

If you happen to be trekking to Madagascar, know that it's big. It’s 592,800 square kilometres (or 226,917 square miles), making it the fourth-largest island on the planet — bigger than Spain, Thailand, Sweden and Germany. The island has an interesting geologic history.

Plate tectonic theory had its beginnings in 1915 when Alfred Wegener proposed his theory of "continental drift."

There have been few attempts apart from McKinley’s (1960) comparison of the Karoo succession of southwestern Tanzania with that of Madagascar to follow the famous geological precept of “going to sea.” One critical reason is that although there may be a bibliography of several thousand items dealing with Madagascan geology as Besairie (1971) claims, they are items not generally available to the general public. The vital information gained of the geology of the offshore area by post-World War II petroleum exploration has remained largely proprietary.

We do know that Madagascar was carved off from the African-South American landmass early on. The prehistoric breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana separated the Madagascar–Antarctica–India landmass from the Africa–South America landmass around 135 million years ago. Madagascar later split from India about 88 million years ago, during the Late Cretaceous, so the native plants and animals on the island evolved in relative isolation.

|

| Red-Tailed Lemurs, Waiwai & Hedgehog |

Today, beautiful outcrops of wonderfully preserved fossil marine fauna hold appeal for me. The material you see from Madagascar is distinctive — and prolific.

Culturally, you'll see a French influence permeating the language, architecture and legal process. There is a part of me that pictures these lovely Lemurs chatting away in French. "Ah, la vache! Regarde le beau fossile, Hérissonne!"

We see the French influence because good 'ol France invaded sleepy Madagascar back in 1883, during the first Franco-Hova War. Malagasy (the local Madagascarian residents) were enlisted as troops, fighting for France in World War I. During the Second World War, the island was the site of the Battle of Madagascar between the Vichy government and the British. By then, the Malagasy had had quite enough of colonization and after many hiccuping attempts, reached full independence in 1960. Colonization had ended but the tourist barrage had just begun. You can't stop progress.

If you're interested in learning more about this species, check out the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part L (Ammonoidea). R.C. Moore (ed). Geological Soc of America and Univ. Kansas Press (1957), p L394. Or head over to look at the 2002 paper from Riccardi and Medina. 2002. Riccardi, A., C. & Medina, F., A. The Beudanticeratinae and Cleoniceratinae (Ammonitina) from the Lower Albian of Patagonia in Revue de Paléobiologie - 21(1) - Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle de la ville de Genève, p 313-314 (=Aioloceras besairiei (COLLIGNON, 1949). You have Bertrand Matrion to thank for the naming correction. Good to have friends in geeky places!

Collignon, M., 1933, Fossiles cenomaniens d’Antmahavelona (Province d’ Analalave, Madagascar), Ann. Geol. Serv. Min. Madagascar, III, 1934 Les Cephalopods du Trias inferieur de Madagascar, Ann. Paleont. XXII 3 and 4, XXII 1.

Besairie, H., 1971, Geologie de Madagascar, 1. Les terrains sedimentaires, Ann. Geol. Madagascar, 35, p. 463.

J. Boast A. and E. M. Nairn collaborated on a chapter in An Outline of the Geology of Madagascar, that is very readable and cites most of the available geologic research papers. It is an excellent place to begin a paleo exploration of the island.

If you happen to parle français, check out: Madagascar ammonites: http://www.ammonites.fr/Geo/Madagascar.htm

Saturday, 8 June 2024

BARNACLES: KWIT'A'A

They choose their permanent homes as larvae, sticking to hard substrates that will become their permanent homes for the rest of their lives. It has taken us a long time to find how they actually stick or what kind of "glue" they were using.

Remarkably, the barnacle glue sticks to rocks in a similar way to how red cells bind together. Red blood cells bind and clot with a little help from some enzymes.

These work to create long protein fibres that first blind, clot then form a scab. The mechanism barnacles use, right down to the enzyme, is very similar. That's especially interesting as about a billion years separate our evolutionary path from theirs.

So, with the help of their clever enzymes, they can affix to most anything – ship hulls, rocks, and even the skin of whales. If you find them in tidepools, you begin to see their true nature as they open up, their delicate feathery finger-like projections flowing back and forth in the surf.

One of my earliest memories is of playing with them in the tidepools on the north end of Vancouver Island. It was here that I learned their many names. In the Kwak'wala language of the Pacific Northwest, the word for barnacles is k̕wit̕a̱'a — and if it is a very small barnacle it is called t̕sot̕soma — and the Kwak'wala word for glue is ḵ̕wa̱dayu.

Friday, 7 June 2024

NEVADA'S UPPER TRIASSIC LUNING FORMATION

Wednesday, 5 June 2024

BLUE JAY: KWAS'KWAS

Sunday, 2 June 2024

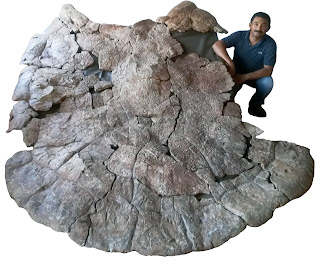

STUPENDEMYS GEOGRAPHICUS: A COLOSSAL TURTLE

These aquatic beasties had shells almost three metres long (up to 9.5 feet) making it about a 100 times larger and sharing mixed traits with some of it's nearest living relatives — the giant South American River Turtle, Podocnemis expansa and Yellow-Spotted Amazon River Turtle, Podocnemis unifilis, the Amazon river turtle, Peltocephalus dumerilianus, and twice that of the largest marine turtle, the leatherback, Dermochelys coriacea.

It was also larger than those huge Archelon turtles that lumbered along during the Late Cretaceous at a whopping 15 feet, just over 4.5 metres. Stupendemys geographicus lived during the Miocene in Venezuela and Columbia. South America is a treasure trove of unique fossil fauna.

Throughout its history, the region has been home to giant rodents and an amazing assortment of crocodylians. It was also home to one of the largest turtles that ever lived. But for many years, the biology and systematics of Stupendemys geographicus remained largely unknown. When we found them in the fossil record it is usually as bits and pieces of shell and bone; exciting finds but not enough for us to see the big picture.

|

| Palaeontologist Rodolfo Sánchez with Stupendemys geographicus |

But for almost four decades, very few complete carapaces or other telltale fossils of Stupendemys were found in the region.

This excited Edwin Cadena, Paleontologist at the Universidad del Rosario in Colombia and researchers of the University of Zurich (UZH) and fellow researchers from Colombia, Venezuela, and Brazil. They had very good reason to believe that it was just a matter of time before more complete specimens were to be found. The area is a wonderful place to do fieldwork. It's an arid, desert locality without plant or forest coverage we see at other sites. Fossils weather out but do not wash away like they do at other sites.

Their efforts paid off and the fossils are marvellous. Shown here is Venezuelan Palaeontologist Rodolfo Sánchez with a male carapace (showing the horns) of Stupendemys geographical. This is one of the 8 million-year-old specimens from Venezuela.

|

| Rodolfo Sánchez with Stupendemys geographicus |

Together, they paint a much clearer picture of a large terrestrial turtle that varied its diet and had distinct differences between the males and females in their morphology. Cadena published in February of this year with his colleagues in the journal Science Advances.

The researchers grouped together from multiple sites to help create a better understanding of the biology, lifestyle and phylogenetic position of these gigantic neotropical turtles.

Their paper includes the reporting of the largest carapace ever recovered and argues for a sole giant erymnochelyin taxon, S. geographicus, with extensive geographical distribution in what was the Pebas and Acre systems — pan-Amazonia during the middle Miocene to late Miocene in northern South America).

This turtle was quite the beast with two lance-like horns and battle scars to show it could hold its own with the apex predators of the day.

They also hypothesize that S. geographicus exhibited sexual dimorphism in shell morphology, with horns in males and hornless females. From the carapace length of 2.40 metres, they estimate to total mass of these turtles to be up to 1.145 kg, almost 100 times the size of its closest living relative. The newly found fossil specimens greatly expand the size of these fellows and our understanding of their biology and place in the geologic record.

Their conclusions paint a picture of a single giant turtle species across the northern Neotropics, but with two shell morphotypes, further evidence of sexual dimorphism. These were tuff turtles to prey upon. Bite marks and punctured bones tell us that they faired well from what must have been frequent predatory interactions with large, 30 foot long (over 9 metres) Caimans — big, burly alligatorid crocodilians — that also inhabited the northern Neotropics and shared their roaming grounds. Even with their large size, they were a very tempting snack for these brutes but unrequited as it appears Stupendemys fought, won and lumbered away.

Image Two: Venezuelan Palaeontologist Rodolfo Sánchez and a male carapace of Stupendemys geographicus, from Venezuela, found in 8 million years old deposits. Photo credit: Jorge Carrillo

Image Three: Venezuelan Palaeontologist Rodolfo Sánchez and a male carapace of Stupendemys geographicus, from Venezuela, found in 8 million years old deposits. Photo credit: Edwin Cadena

Reference: E-A. Cadena, T. M. Scheyer, J. D. Carrillo-Briceño, R. Sánchez, O. A Aguilera-Socorro, A. Vanegas, M. Pardo, D. M. Hansen, M. R. Sánchez-Villagra. The anatomy, paleobiology and evolutionary relationships of the largest side-necked extinct turtle. Science Advances. 12 February 2020. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aay4593

Saturday, 1 June 2024

HETEROPTERA: SNEAKOPTERA

The Green River Formation is an Eocene geologic formation that records a 12 million year history of sedimentation in a group of intermountain lakes in three basins along the present-day Green River in Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah. It is one of the most important outcrops we have for insight into life in the Eocene. It gives a window into what our world looked like about 50 million years ago.

.png)