Located three hours east of Vancouver, most folks head to Harrison Lake to enjoy its crisp waters, soak in the hot springs, camp or four-wheel-drive immersed in rugged scenery, or look for the elusive Sasquatch reported to live in the area.

But there are some who come to Harrison Lake and miss the town entirely. Instead, they favour the upper west side of the lake and the fossiliferous bounty found here.

Indeed, this is the perfect location for local citizen scientists to strut their stuff. Harrison is a perfect family day trip, where you can discover wonderful marine fossil specimens as complete or partially crushed fossilized shells embedded in rock.

It is truly amazing that we can find them at all. These beauties range in age from Jurassic to Cretaceous, with most being Lower Callovian, meaning the ammonites here swam our ancient oceans more than 160 million years ago.

The area around Harrison Lake has been home to the Sts’ailes, a sovereign Coast Salish First Nation for thousands of years. Sts’ailes’ means, “the beating heart,” and it sums up this glorious wilderness perfectly. They describe their ancient home as Xa’xa Temexw or Sacred Earth.

With the settling of Canada, Geologists began exploring the area in the 1880s, calling upon the Sts’ailes to help them look for coal and a route for the Canadian Pacific Railway. Coal was the aim, but happily, they also found fossils. Sacred Earth, indeed.

|

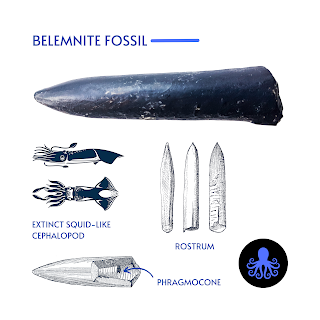

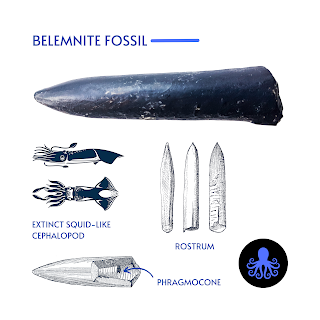

| Belemnite Fossils |

In my favourite outcrops, you can find large, smooth inflated Jurassic ammonites along with their small grey and brown cousins.

Further up the road, you will see Cretaceous cigar-shaped squid-like cephalopods called Belemnites, and the bivalve (clam) Buchia — gifts deposited by glaciers. Here are the most common.

Ammonites

Almost all of the ammonite specimens found near Harrison Lake are the toonie sized Cadoceras (Paracadoceras) tonniense with well-preserved outer whorls but flattened inner whorls. We find semi-squished elliptical specimens here, too. If you see a large, smooth, inflated grapefruit-sized ammonite, you are holding a rare prize — a Cadoceras comma ammonite, the macroconch or female of the species.

Ammonites were predatory, squid-like creatures that lived inside coil-shaped shells. Like other cephalopods, ammonites had sharp, beak-like jaws inside a ring of squid-like tentacles that extended from their shells. They used these tentacles to snare prey — plankton, vegetation, fish and crustaceans — similar to the way a squid or octopus hunts today.

Within their shells, ammonites had a number of chambers called septa filled with gas or fluid, and they were interconnected through a wee air tube. By pushing air in or out, they were able to control their buoyancy.

These small but mighty marine predators lived in the last chamber of their shell and continuously built new shell material as they grew. As they added each new chamber, they would move their squid-like body down to occupy the final outside chamber.

Interestingly, ammonites from Harrison Lake are quite similar to the ones found within the lower part of the Chinitna Formation near Cook Inlet, Alaska, and Jurassic Point, Kyuquot, on the west coast of Vancouver Island — some of the most beautiful places on Earth.

Buchia (bivalve) Clams

The bivalve or clam Buchia are commonly found at Harrison Lake. You will see them cemented together en masse. . They populated Upper Jurassic–Lower Cretaceous waters like a team sport. When they thrived, they really thrived, building up large coquinas of material. Large boulders of Buchia cemented together en masse hitched a ride with the glaciers and were deposited around Harrison Lake. Some kept going and we find similar erratics or glacier-deposited boulders as far south as Washington state.

Buchia is used as Index Fossils. Index fossils help us to figure out the age of the rock we are looking at because they are abundant, populate an area en masse, and then die out quickly. In other words, they make it easy to identify a geologic time span.

So what does this mean to you? Now, when you are out and about with friends and discover rocks with Buchia, or made entirely of Buchia, you can say, “Oh, this looks to be Upper Jurassic or Lower Cretaceous. Come take a look! We're likely the first to lay eyes on this little clam since dinosaurs roamed the Earth.”

Fossil Collecting at Harrison Lake Fossil Field Trip — Getting there

This Harrison Lake site is a great day trip from Vancouver or the Fraser Valley. You will need a vehicle with good tires for travel on gravel roads. Search out the route ahead of time and share your trip plan with someone you trust. If you can pre-load the Google Earth map of the area, you will thank yourself.

Heading east on from Vancouver, it will take you 1.5-2 hours to reach Harrison Mills.

Access Forestry Road #17 at the northeast end of the parking lot from the Sasquatch Inn at 46001 Lougheed Hwy, Harrison Mills. From there, it will take about an hour to get to the site. Look for signs for the Chehalis River Fish Hatchery to get you started.

Drive 30 km up Forestry Road #1, and stop just past Hale Creek at 49.5° N, 121.9° W (paleo-coordinates 42.5° N, 63.4° W) on the west side of Harrison Lake. You will see Long Island to your right.

The first of the yummy fossil exposures are just north of Hale Creek on the west side of the road. Keep in mind that this is an active logging road, so watch your kids and pets carefully. Everyone should be wearing something bright so they can be easily spotted.

How to Spot the Fossils

The fossils here are easily collected—look in the bedrock and in the loose material that gathers in the ditches. Specimens will show up as either dark grey, grey-brown or black. Look for the large, dark-grey boulders the size of smart cars packed with Buchia.

And while you are at it, be on the lookout for anything that looks like bone. This site is also ripe for marine reptiles—think plesiosaur, mosasaur and elasmosaur. As a citizen scientist and budding palaeontologist, you might just find something new!

What to Know Before You Go

Fill your gas tank and pack a tasty lunch. As with all trips into British Columbia's wild places, dress for the weather. You will need hiking boots, rain gear, gloves, eye protection, and a good geologic hammer and rock (cold) chisel.

Wear bright clothing and keep your head covered. Slides are common, and you may start a few if you hike the cliffs. If you are with a group, those collecting below may want to consider hardhats in case of rockfall — chunks of rock the size of your fist up to the size of a grapefruit. They pack a punch.

Bring a colourful towel or something to put your keepers on. Once you set rock down, it can be hard to find again given the terrain. I take the extra precaution of spraying the ends of my hammers and chisels with yellow fluorescent paint, as I have lost too many in the field. You will also want to bring a camera for the blocks of Buchia that are too big to carry home.

Identifying Your Treasures

When you have finished for the day, compare your treasures to see which ones you would like to keep. In British Columbia, you are a steward of the fossil, which means they belong to the province, but you can keep them safe. You are not allowed to sell or ship them outside British Columbia without a permit.

Once you get home, wash and identify your finds. Harrison Lake does not have a large variety of fossil fauna, so this should not be difficult. If your find is coiled and round, it is an ammonite. If it is long and straight, it is a belemnite. And if it looks like a wee fat baby oyster, it is Buchia. This is not always true, but mostly true.

What about collecting fossils in all seasons?. Everyone has a preference. I prefer not to collect in the snow, but I have done it. While sunny days are lovely, it can also be easier to see the specimens when the rock is wet. So, do we do this in the rain? Heck, yeah!

In torrential rain?

Yes — once you are hooked, but for your casual friends or the kiddos, the answer is likely no. Choose your battles. They may come with you, but a cold day getting soaked is no fun.

In time, you will find your inner fossil geek — probably with your first find. And that's just the tip of the iceberg. First, it will be you, then your kids, your friends and then your neighbour. Once you start, it is easy to get hooked. Fossil addiction is real, and the only cure is to get out there and do it some more. You've got this!

References and further information:

A. J. Arthur, P. L. Smith, J. W. H. Monger and H. W. Tipper. 1993. Mesozoic stratigraphy and Jurassic palaeontology west of Harrison Lake, southwestern British Columbia. Geological Survey of Canada Bulletin 441:1-62

R. W. Imlay. 1953. Callovian (Jurassic) ammonites from the United States and Alaska Part 2. The Alaska Peninsula and Cook Inlet regions. United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 249-B:41-108

An overview of the tectonic history of the southern Coast Mountains, British Columbia; Monger, J W H; in, Field trips to Harrison Lake and Vancouver Island, British Columbia; Haggart, J W (ed.); Smith, P L (ed.). Canadian Paleontology Conference, Field Trip Guidebook 16, 2011 p. 1-11 (ESS Cont.# 20110248).

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)